Ressourcement is Dead. Long Live Ressourcement!

Understanding what ressourcement isn't might just be the key to its renewal.

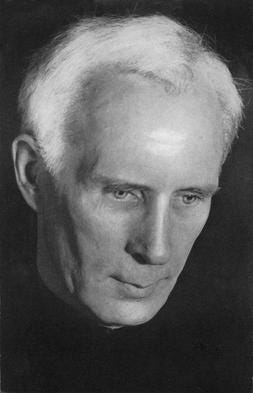

I started graduate school enamored with Henri de Lubac and the ressourcement movement of which he was a part. I still love de Lubac and ressourcement, but I also kind of wish we’d stop talking about it, because most of what gets labeled ressourcement isn’t, and a lot of applications of ressourcement so construed are actually harmful. Allow me to explain.

There’s a sort of workaday notion of the ressourcement project that conceives of it as a matter of retrieval and/or repristination of the theological achievements of times past. Thus, any reading of patristic figures or attempt to ressucitate outlooks or practices from bygone times gets called ressourcement, as if it were a matter of reading Irenaeus or Augustine or Origen or Jerome and concluding with a “go and do likewise.”

On the one hand, this construal is understandable. Jean Daniélou’s programmatic essay, “Les orientations présentes de la pensée religieuse” (Études, 1946) notes a turn toward Scripture, patristics, and the liturgy as genuine theological sources. And such luminaries as Daniélou, de Lubac, Marie-Dominique Chenu, and Yves Congar produced monumental historically-oriented figures of the oft-forgotten Christian past, and particularly ways in which it could shed light on the problems of their — and, by extension, our — Christian present.

I believe that this narrative also leads to the present state of affairs wherein ressourcement is largely defunct, with the exception of reactionary-revanchist circles (to whom I shall return below). As one of my grad school mentors frequently noted, Vatican II was at once the triumph and the swan song of ressourcement. The projects and outlooks of figures who’d been treated with suspicion if not outright silenced by the Catholic hierarchy became the commonly accepted mainstream, with the council’s documents breathing the essayistic, narratival mark of the ressourcement. And yet, after the council, it’s difficult to find anyone actually engaged in the sort of work that led to and informed the council. Ressourcement is dead.

On the other hand, this construal misses the point. Of the ressourcement figures, I know de Lubac best (with Congar a distant second), so I’ll focus on him. Throughout de Lubac’s career, he endeavored to inject a historical consciousness into Catholic theology, meaning among other things the recognition that there are no timeless truths, that (as his Jesuit confrère Bernard Lonergan would put it) “doctrines have dates”), that there is indeed such thing as historical development and change, meaning that our situation is not the same as Irenaeus’s, or Thomas Aquinas’s, or Hugh of St. Victor’s, or Cajetan’s, or de Lubac’s. History’s flow is unstopping, and historical change means that we cannot simply reproduce the outlooks and approaches of the past — even if they were good and faithful, even if they were better and more faithful than our own! — because they belong to the past and are inadequate to the task of the present.

This is seen with particular clarity in his works on the spiritual interpretation of Scripture (a practice with which he was enamored, and which he also insists cannot be reproduced in our own day, at least not in any straightforward manner), and in his The Splendor of the Church, where he warns against “a cult of nostalgia, either in order to escape into an antiquity he can reshape as he likes or in order to condemn the Church of his own day,” and calls for a skepticism “about those myths of the Golden Age which give such a stimulus to the natural inclination to exaggeration, righteous indignation, and facile anathematizing,” not recognizing that Christ is always present with and guiding his church through the Holy Spirit (pp. 242–43).

Thus, if we turn to the past in order to repudiate the present, or to reproduce that past in the present, we betray both our historical foundations and the demands of the present moment. One can see, I hope, the way this outlook leads to the post-conciliar death of ressourcement. If our historical turn is so that we can bring that history into the present and correct our course in light of it, and if Vatican II did so, then ressourcement has accomplished its task and can now go gentle into that good night.

And if that’s what ressourcement is, then good riddance.

Because, if that’s what ressourcement is, then at its best it attempts an impossibility — we can never arrest nor reverse the flow of history — and frequently enough what it actually does accomplish harmful and problematic. I mentioned above revanchist appeals to the past, ranging from populist nostalgia of Make America Great Again, which ignores (when it does not actively pine for) the overt racism, sexism, and homophobia of the American past (which is not at all to say that these are problems of the past which no longer plague our present), to the elitist’s calls to RETVRN to tradition. Both seek to upend progress, to live in a world that no longer exists (if it ever did…most of these reconstructed pasts to which we’re told to revert are little more than illusory projections), and to do so at the expense of vulnerable members of the community.

In this connection, it’s also worth noting the Eurocentrism and coloniality of so much of the original ressourcement outlook. I raise this, not to cast aspersions. I’m not sure what else we’d expect from a bunch of early-twentieth-century Frenchmen (and, they were pretty much exclusively French men). But we operate within a different cultural context than them, one where we’ve learned to interrogate colonialism and Eurocentrism, and to broaden our horizons to include the experience and questions of a wider swath of the human family. We pay no honor to our ressourcement era forebears by glossing over their complicity in the colonial project, or by refusing to scrutinize them on this front. One of my next projects, which I’m still trying to figure out how to execute, will be a dialectical application of ressourcement and liberationist and post/de-colonial outlooks, so that ressourcement can be in service to liberation, while being itself liberated from its own colonialist strictures.

And with that, I’m ready to say something about what ressourcement actually is. My study of Henri de Lubac’s theology persuaded me that his forays into history were not at all motivated by nostalgia, nor aimed at retrieval or repristination, instead, they were driven by the conviction that the heart of all Christian reality is the mystery of redemption in Jesus Christ, the Word made flesh, crucified and raised for us and our salvation. This mystery is infinitely rich, perpetually valid, always beckoning us to enter more deeply into it, and, in so entering it to enter into the life of God the Trinity. De Lubac’s historical consciousness operated according to the conviction that history is real, with real, irreversible changes, and also that the decisive change has already occurred in the mystery of Christ. All authentic development within the Christian tradition is interior to and the unfurling of this most fundamental change.

And so we turn to the past not to recreate it, nor because we think our forebears were smarter or more faithful than we are (in some cases, perhaps, they were, in others, decidedly not…it wasn’t until well into the 20th century that the Catholic Church definitively repudiated slavery as an objective evil), but because they witnessed to this mystery within their contexts, and by attending to this witness, we can deepen our own insight into the mystery, to which we must continually turn if we are to be faithfully and authentically Christian in our own day. This turn to the past gains us insight, but such insight cannot substitute for our own responsible agency here and now.

And with this understanding of ressourcement we are led to a recognition that the ressourcement project must burst its own seams, must expand beyond its sometimes narrowly-defined “canon,” because the one indispensable canon is the mystery of Christ. All other sources gain their validity from their inhabiting of this mystery. This ought to lead to our asking, “To whose witness have we not attended? Whose voices must be heard so that we can learn the truth of Jesus from them as well?”

Thus, an authentic ressourcement will lead us to attend to the voices and outlooks of those historically marginalized within our cultures and within theological discourse, because only together with “all the saints” can we grasp “the breadth and length and height and depth” of “the love of Christ that surpasses all knowledge, so that [we] may be filled with all the fullness of God” (Eph. 3:18–19).

So, yes, ressourcement is dead, and, to an extent, good riddance. But all the same, long live ressourcement!