Violence, Rhetoric, and Truth

Call a spade a spade and the Trump administration fascist

My heart immediately sank when I received the news alert that Charlie Kirk had been shot, and those feelings only intensified as I continually refreshed my news feed until finally receiving the confirmation that the shooting had been fatal. My dismay had several reasons. The most important one is that it’s simply horrible for anyone to be murdered.

Beyond that, though, I felt dread in seeing yet another episode of political violence, and trepidation at how the regime propagandists would utilize his murder to clamp down on opposition. Many invocations of Horst Wessel and the Reichstag Fire circulated that day, and for good reason. That evening President Trump addressed the nation, blaming Kirk’s death on “the left,” and our rhetoric, including our (accurate) comparison of the present regime to the Nazis. It didn’t matter that the killer was still at large, that no one knew who they were or what motivated them. The narrative of the violent left in need of suppression was already being constructed, and facts need not get in the way.

That day and the next, my wife scrolled through Facebook, distraught by how many acquaintances from our past—folks we used to go to church with—were calling for blood, apparently in the name of Jesus.

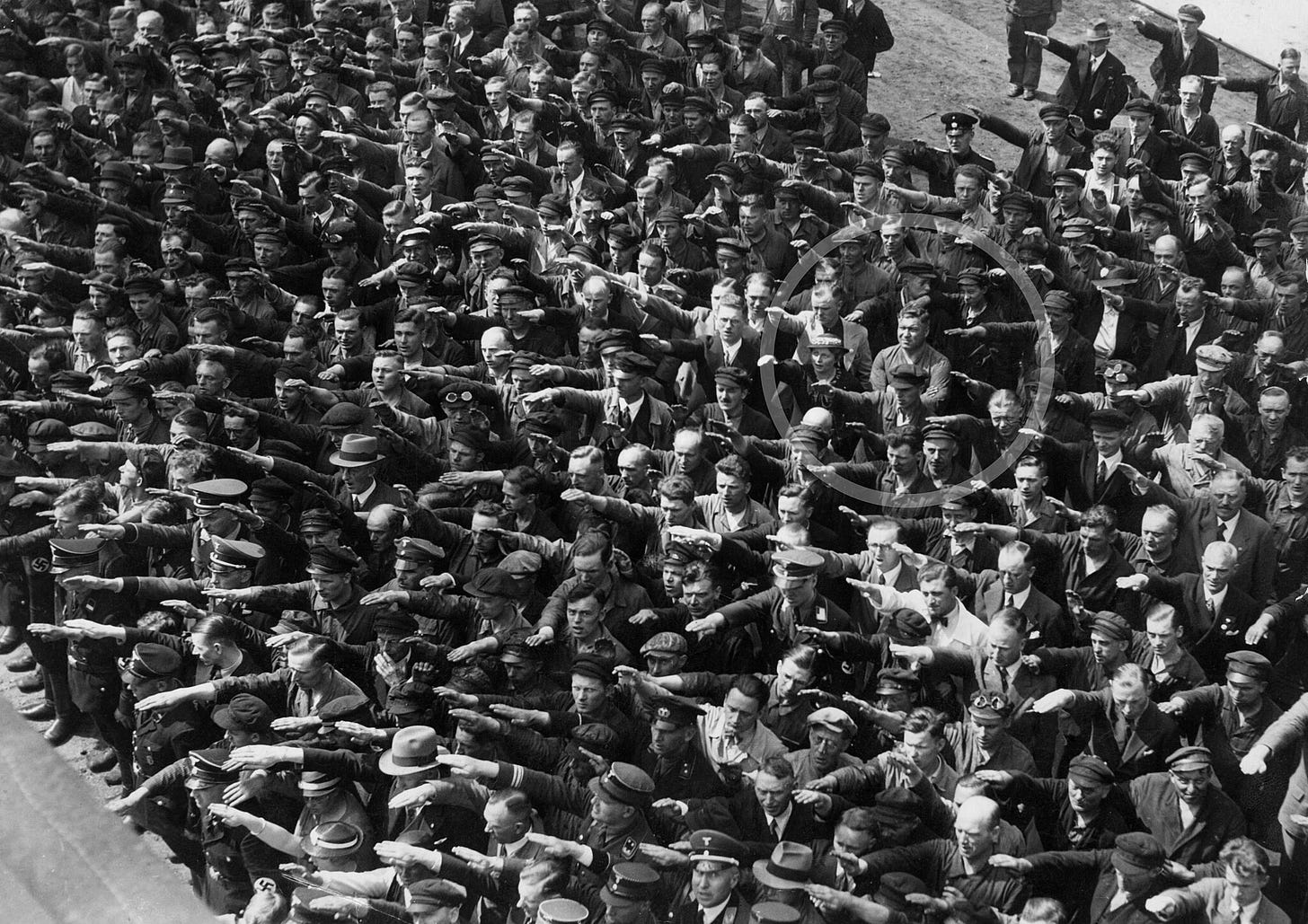

The coming days saw threats of violence against Historically Black Colleges and Universities, demonstrations from Kirk devotees chanting things like “fight back, white man,” and targeted efforts for people to lose their jobs if they said the wrong things about Kirk (because no one loves cancel culture more than the right wing). We saw Jimmy Kimmel be suspended and then eventually reinstated, while Kirk’s funeral took the form of a Nazi rally.

I don’t at all want to take away from the genuinely touching moment when his widow, Erika Kirk said, through tears, that she forgives Charlie’s murderer, imploring that only love can heal, that hate can never be the answer. If only that had been the consistent message. Instead, Donald Trump received thunderous applause when he explained that he despises his enemies and wishes us harm, as did Stephen Miller, who, in full Goebbels mode, preached the false gospel of blood and soil, denouncing the regime’s opponents as “nothing” and warning of the retribution to come.

Then on September 24 an attack on an ICE facility in Texas left one detainee dead and two more critically injured, before the shooter took his own life. The regime’s propagandists are attributing the attack to antipathy towards ICE, blaming “the left” for (accurately) likening them to the Gestapo. It’s possible that they’re right about the assailant’s motives: maybe he went there targeting law enforcement and is just bad at aiming. But because the Justice Department has been purged of its non-partisan character, stacked with loyalists (of dubious competence and even lesser trustworthiness), I’m left to wonder. Similarly with Kirk’s murderer. Everything about him screams “groyper,” as far as I can tell, but officials are claiming that he was radicalized to a far-left ideology. Meanwhile the studies that have demonstrated that by far and away most political violence is carried out by right-wing white men are being scrubbed from the internet. It would be really nice to be able to trust what we’re being told, but I digress.

In the end, it doesn’t matter what motivated these men. The violence they carried out still happened. The lives they’ve taken have now ended. Families are now bereft of loved ones. We are facing an increase in political violence: from the violent insurrection fomented by Donald Trump on January 6, 2021; to the vicious attack against Paul Pelosi; to the murders of Melissa and Mark Hortman; to the murder of Charlie Kirk; to the shooting of ICE detainees; to the terrorizing and kidnapping carried out by ICE agents; or the extrajudicial killing of suspected drug smugglers in a military operation that was probably a war crime.1

Similarly, there has been an uptick in incendiary rhetoric, from JD Vance demonizing Haitian refugees, falsely accusing them of eating household pets (and admitting that he’d fabricated the story in order to draw attention to people’s concerns), to Trump calling immigrants vermin, to Stephen Miller’s funeral speech, and, yes, to people on the left saying hateful things, including making light of Charlie Kirk’s murder.

All of this has led me to reflect on my own practices in the current situation. Particularly, as people are getting targeted for what they say on social media, I want to be sure I don’t set myself up for trouble. At the same time, I’ve learned enough from reading Timothy Snyder to know that one of the worst responses to tyranny is giving into the impulse to obey in advance. Silencing ourselves in fear of retribution just paves the way for the authoritarians to continue without opposition. I am confident that this regime will fail. I pray for that every day. And when it fails, when the verdict of history is given, I want to have been working in opposition to it. “One day everyone will have always been against this,” and I want to be on record now that there were people who were opposed all along, and who tried to do what’s right in the face of encroaching fascism.

I’m not going to stop calling these Nazis Nazis. The shoe fits and it’s high time that we tell the truth about what’s going on. I’ve spent most of the last year studying fascism and the more I learn the more distraught I am by how accurate the description is, by how closely the playbook being used by the Trump administration echoes the playbooks used by the last century’s fascist movements. And here it’s important to note again, that when I call Trump supporters Nazis, I’m not insulting them, I’m accurately describing the movement. We tend to think of Nazis as inhuman monsters, but Hannah Arendt has exposed the “banality of evil.” You don’t have to be an inhuman monster to be party to atrocity; you just have to be indifferent. (In some ways, it would be better to be an inhuman monster, because at least then you’d stand for something.) I’ll stop calling this movement fascist if it ever stops being fascist.

While the Trump regime is trying to eliminate this comparison, blaming it for violence, you can only see this as promoting violence if you give into the idea that the way to a better world lies in eliminating certain kinds of people. That’s an idea I’ve worked tirelessly against, especially in my teaching. It is the logic by which the Trump regime operates (working to purge our country of migrants, of LGBTQ people, of “the left,” of autistic people), but that’s precisely the problem I’m trying to oppose. We’ll win not by the elimination of racists and homophobes and Trump supporters, but by conversion of heart and mind: Erika Kirk’s message, not Stephen Miller’s.

But as I’ve reflected, I can see ways I need to do better in my rhetoric. As the regime has progressed, as things have gotten so much worse than I anticipated (and I expected them to be really bad), I’ve given into frustration. Disgusted by the hypocrisy and/or indifference of Trump supporters, finding the few of them that I know unwilling to engage in conversation about what’s happening, realizing that no amount of evidence or reasoning was going to break through to them,2 I’ve resorted to mockery quite a few times. In my vexation, I’ve used social media to express my disdain and contempt, and done so in deliberately provocative ways (I guess we’re not going to have a conversation, but I can make sure that you see this). In hindsight, I can recognize that this is counterproductive. I might have derived some Sisyphean satisfaction from it, but I doubt it’s moved the needle in any meaningful way in terms of making the world better. And in our days of targeting dissent, it’s also a dangerous practice.

I know that I need to speak up and speak out and take action, but most of that needs to happen in the real world anyway.

So I plan on dialing back my social media activity and sticking mainly to longer form writing, which allows for greater nuance, greater thoughtfulness, less impulsivity. And in all of this, I hope that I can play some small part in hastening the end of this evil regime by helping to change minds and through the democratic process, and in fostering greater thoughtfulness and commitment to justice.

This reminds me of the late, great James Cone’s assertion that the question of whether or not the struggle for Black liberation must be committed to non-violence was very much a white question, one that ignores the violence carried out against the Black community. Calling for nonviolence is all well and good, and, I would hasten to add, urgent in our current context, but we shouldn’t pretend that we’re living in a situation of nonviolence. It’s just a question of whose violence counts as violence, and whose is invisible or celebrated as good. Would that we were all committed to nonviolence.

And, really, I should have realized this from the beginning. These are, people, after all, who were willing to vote for a rapist. When someone’s moral compass is so debased that they’ve decided rape isn’t especially bad after all, there’s really nothing I can say to persuade them that the administration’s policies are bad.

A staunch and clear-eyed post. I think your movement to long-form response rather than social media reactions is a wise one, and one I try to share with you through my fiction. IMHO, this is your money quote: "We’ll win not by the elimination of racists and homophobes and Trump supporters, but by conversion of heart and mind: Erika Kirk’s message, not Stephen Miller’s."